Catherine the Great before she was Great in 1760

- jimmoyer1

- Aug 17, 2024

- 17 min read

Updated: Sep 24, 2024

By Spring of 1760 Catherine had assembled 3 powerful influencers all not knowing of the other. They were the Orlov brothers, former Russian Ambassador to Sweden Nikita Panin, and Dashkova, younger sister to Peter III's mistress. All were poised to strike, but not yet.

While George Washington is in his 2nd year as a representative of Frederick County Virginia in the House of Burgesses, Catherine is learning, planning, observing and organizing. Catherine was born Princess Sophie Augusta Frederica von Anhalt-Zerbst (2 May 1729 – 17 November 1796). She is 3 years older than George Washington. In 1760, he's 28. She is 31. She was 62 when she hired John Paul Jones in the Russo-Turkish War. The Crimea was won then. Also under her reign, Poland vanished when Russia, Austria and Prussia each took a piece of it. She also withdraws support for Prussia, undoing her deposed husband's alliance with Prussia.

Elizabeth Dies

Empress Elizabeth, the leader of Russia, dies 25 Dec 1761 (new 5 Jan 1762).

Peter III, the husband of Catherine, is made Emperor, who promptly switches sides to support Prussia and against France and Austria.

Catherine finds this moment of Empress Elizabeth's death to mourn in public by wearing a black ensemble that covers her pregnancy with Grigori Orlov, reputed for his enormous male endowment and his popularity with the Russian elite and the Russian military. His brothers are also influential and supporters of Catherine.

About the Date confusion

The Gregorian calendar was implemented in Russia on 14 February 1918 by dropping the Julian dates of 1–13 February 1918 pursuant to a Sovnarkom decree signed 24 January 1918 (Julian) by Vladimir Lenin.

The British empire adopted the Gregorian Calendar in 1752, dropping 11 days in September 1752, when Winchester VA was officially established as the name of Winchester.

The Coup

It isn't until 28 June 1762 (new 9 July 1762) Catherine's 3 groups of allies initiate the coup against her husband, Tsar Peter III, grandson of Peter the Great. Frederick the Great, appreciated Emperor Peter III for siding with him. Formerly, under Empress Elizabeth, Russia was an enemy in the Seven Years War. But Frederick the Great knew how weak and misguided Peter III was. He remarked "“[Peter] allowed himself to be dethroned like a child being sent to bed.”

That's it.

That's our lead story.

There's always more.

Skip around.

Read bits and pieces.

Compiled by Jim Moyer 8/17/2024, researched in 2023, update 8/19/2024

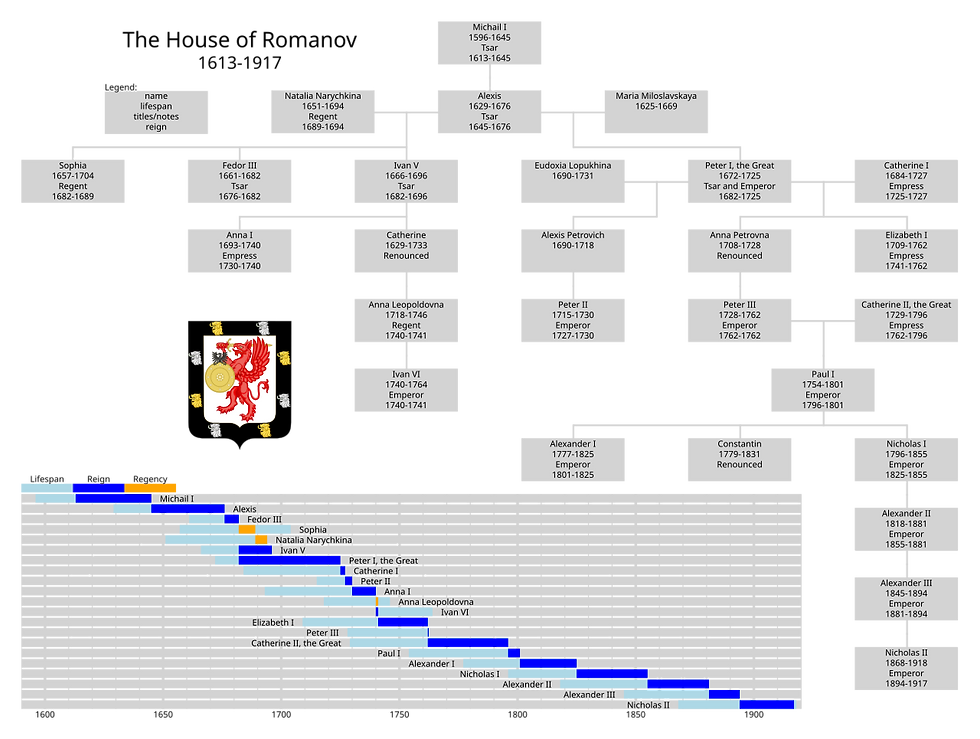

Table of Contents

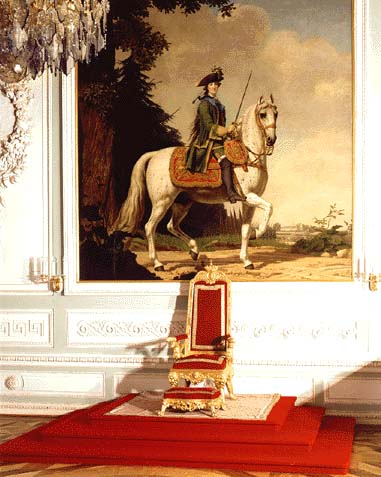

Portrait

Catherine used portraits as a way of influencing others of her status.

She obtains the services of the artist for the late Empress Elizabeth. He is Danish Artist, Virgilius Ericksen.

!2' by 11' size portrait of Catherine the Great on her horse, Brilliant.

Picture is located in the Throne Room or Great Hall at the Grand Palace in Peterhof

Catherine's 3 groups of allies in 1760

us

Orlovs

Gregori Orlov was a war hero when Russia was fighting Prussia. He was known for both his Mars and Venus conquests. He was wounded 3 times in the battle of Zorndorff 25 Aug 1758. He returned to Petersburg high society from the battles against Prussia in March 1759.

"Orlov's political potential in Catherine's eyes, almost equalled his sexual prowess. He was 100 percent Russian and a military hero. He and his 4 brothers, the energetic Aleksei above all, were the darlings of the capital's four elite Guards regiments, which comprised the flower of the Russian nobility. They were young, patriortic, and politically malleable, with loyalties to persons more than to theoretical principles or particular court parties. They were ambitious for prestige and creature comforts, and thus welcomed the flattering attentions and monetary incentives dispensed by the charmingly cultivated Grand Duchess [Catherine the Great's current title]. In short, Orlov, provided Catherine with a perfect bridge to strategically placed military-political muscle."

page 56

Catherine the Great: Life and Legend Hardcover – November 3, 1988 by John T. Alexander (Author)

Aleksi Orlov had a scar and was known as scarface.

There were 2 other Orlov brothers who also helped Catherine's takeover.

Nikita Panin

Russian Ambassador to Sweden 1748-1760.

Nikita Panin had enjoyed a long friendship with Empress Elizabeth but he shared with Catherine a dislike of " the disarray of Elizabeth's government and the overwhelming overwheening influence of the Shuvalovs and Vorontovas." despite both Elizabeth and Vorontova backing him. Vorontove was also the Uncle of another ally Dashkova.

page 56-57

Catherine the Great: Life and Legend Hardcover – November 3, 1988 by John T. Alexander (Author)

Dashkova

"Another sign of Catherine's search for political supporters was her patronage of Princess Ekaterina Dashkova, the married younger sister of Peter's mistress. In the summer of 1761 while the Empress stayed at Peterhof and the Grand Duchess [Catherine] at Oranienbaum, Princess Dashkova lived between them at the dacha of her uncle, Chancellor Vorontsov, Catherine encouraged young Dashkova's love for reading and occassionally invited her to shared the evening's company at Oranienbaum. Disgusted with her sister's pandering to the course Grand Duke [the future Emporer Peter III], Dashkova sympathized with the refined Grand Duchess [Catherine] and saw in her a worthy model of culutred descorum. She was completely unaware of Orlov's place in her heroine's [Catherine] life and plans for the future. Dashkova could provide valuable intelligence about the machinations of her sister and the entire Voronstov "party.""

page 57

Catherine the Great: Life and Legend Hardcover – November 3, 1988 by John T. Alexander (Author)

Dashkova's husband offered to help Catherine take over power the day Catherine's husband, Peter III, was proclaimed Emporer. But Catherine had gained politcal maturity and caution after 17 years of living in Russia.

"That day she [Catherine] donned a commodious black dress of mourning [of Empress Elizabeth's passing] that she wore through out her husband's 6 month reign. Her swollen shape [being pregnant from Grigori Orlov] thus concealed, she began an assiduous vigil at Elizabeth's bier (despite the stench of the corpse) and after the funeral withdrew from everyday court life."

page 57

Catherine the Great: Life and Legend Hardcover – November 3, 1988 by John T. Alexander (Author)

Six months into the reign of Peter III the coup occurs:

During the coup, Catherine famously rode out at the head of Russia’s army while wearing a man’s military uniform, symbolically presenting herself as a more competent leader than Peter. It was a clever romantic setup that Dashkova duly copied. “Here I was, dressed in uniform, with the red ribbon across my shoulder without its star, a spur upon one heel, and looking like a boy of 15 years of age,” the princess recalled in her memoirs. Within days, the deposed czar was dead; though the official cause was listed as “hemorrhoidal colic,” uncertainty surrounds Peter’s demise, with potential explanations ranging from assassination to suicide. ---- See Article.

Dashkova becomes quite respected in the world of science.

In January 1783, the princess was appointed director of the Imperial Academy of Arts and Sciences (known now as the Russian Academy of Sciences) by Catherine the Great.[6] She became the first woman in the world to head a national academy of sciences. Famous in her own right as a philologist, she guided the ailing Academy to prominence and intellectual respectability. In October 1783, Yekaterina was also named the first president of the newly created Russian Academy and launched a project for the creation of a 6-volume dictionary of the Russian Languages in 1789.[6] In 1783, she was the first foreign woman elected an honorary member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and was invited by her friend Benjamin Franklin to become the first woman to join the American Philosophical Society in 1789. -- wikipedia

Sources

Catherine the Great

Catherine the Great: Life and Legend Hardcover – November 3, 1988

by John T. Alexander (Author)

The Expansionist Policy of Catherine the Great towards the Ottoman Empire (1763-1796)

Catherine's allies

Grigori Orlov

Alexei Orlov

Quote of Scarface

The Orlov Diamond

Nikita Panin

Princess Dashkova

This Russian Noblewoman, Beloved by Catherine the Great and Benjamin Franklin, Embodied the Age of Enlightenment

Empress Elizabeth

Danish Artist for both Elizabeth and Catherine, between 1757 and 1772 he traveled and worked in Saint Petersburg where he became the imperial court painter.

Russia accepts Gregorian Calendar

Frederick the Great

Emporer Peter III

Peter the Great Palace

Potemklin was a lover of Catherine and her leading military commander

The Myth of Catherine the Great and the Horse: A Critical Review of the Historiography

John Paul Jones' Russian service

(born March 28 [March 17, old style], 1743/44, St. Petersburg—died January 16 [January 4, O.S.], 1810, near Moscow)

About the Date confusion

The Gregorian calendar was implemented in Russia on 14 February 1918 by dropping the Julian dates of 1–13 February 1918 pursuant to a Sovnarkom decree signed 24 January 1918 (Julian) by Vladimir Lenin.

The British empire adopted the Gregorian Calendar in 1752, dropping 11 days in September 1752, when Winchester VA was officially established as the name of Winchester.

The article:

If not for her many accomplishments, Ekaterina Dashkova would have been a footnote in history, remembered merely as the younger sister of the mistress of Peter III, the Russian czar deposed by his better-known wife, Catherine the Great. Perhaps motivated by the prospect of this unflattering legacy, the Russian noblewoman—commonly called Princess Dashkova—strove to make a name for herself in the fields of politics, science, philosophy, literature and music, breaking free from the conventions that limited 18th-century women to restrictive gender roles.

Dashkova racked up titles and milestones like her close friend Catherine racked up lovers. She was the first female director of a national scientific academy, one of the first European women to hold government office and the first female member of the American Philosophical Society. She was also the co-founder and president of the linguistics-focused Russian Academy; the author of plays, speeches, letters, essays and a memoir; a journal and dictionary editor; and a composer of arias, songs and hymns. Nowadays, observers might call someone of such varied talents a Renaissance woman, but more accurately, Dashkova was a living symbol of the Russian Enlightenment, which saw Russia compete for the title of most advanced country in Europe.

Before Dashkova became an Age of Enlightenment powerhouse, she had to be properly enlightened. In the 18th century, Europeans were divided on whether girls should be educated. Though great minds like British philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft campaigned for women’s scholarship, public opinion was generally against rearing daughters for work outside of the service industry, or even encouraging open-minded thought. No set curriculum existed, and the only subjects considered necessary for middle- and upper-class girls were needlework, reading, writing, etiquette, music and a bit of arithmetic. Only occasionally would extra subjects be added to young women’s schooling, mainly if their guardians felt the money and effort were worth it.

A 1784 painting of Princess Dashkova Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Peter III and Catherine the Great Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Dashkova was lucky enough to be born into an aristocratic set that had the means, resources and liberal mindset required for a more extensive education. But her relatives had a selfish motive: to prepare their blue-blooded daughters for life at Russian court, where they would be expected to not only serve as their family’s representatives but also use their cleverness to increase the family’s prestige. The sisters’ expensive upbringing was an investment that would yield returns when they made advantageous social connections and secured grand marriages to noblemen.

Dashkova’s early life

Dashkova was born Ekaterina Romanovna Vorontsova in St. Petersburg in 1743. Her parents were a Russian count and a merchant’s daughter whose massive dowry elevated her to the aristocracy. During Dashkova’s youth, she and her two sisters were farmed out to wealthier relatives—a common practice among nobility at the time—for the best possible upbringing in preparation for their already decided future. Under the guardianship of her uncle Mikhail Vorontsov, a Russian statesman who for a time served as the imperial chancellor, Dashkova studied languages, mathematics and literature, developing a particular interest in French philosophy. (Voltaire would become one of her favorite thinkers.) Astute for her age, she impressed her elders, who made note of her aptitude for all subjects, including politics. She seemed to genuinely enjoy her studies and intellectual pursuits.

Yet Dashkova was forced to remain perpetually conscious of the danger of learning too much and potentially driving away male suitors with her intimidating intelligence. Biographer Alexander Woronzoff-Dashkoff describes Dashkova’s situation as a treacherous balancing act in which she felt compelled to cultivate her mind and image to meet upper-class standards, as well as her family’s expectations.

“She was confronted by the discrepancies between her gender and her social goals, between her longing for self-affirmation and the requirements of a socially acceptable self-effacement, between a private and public life, and between a desire for public recognition and the more culturally appropriate roles for female behavior,” writes Woronzoff-Dashkoff in Dashkova: A Life of Influence and Exile.

Dashkova's uncle, Mikhail Vorontsov Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

A tapestry of Dashkova's scandalous sister, Elizaveta Metropolitan Museum of Art under public domain

In 1758, Dashkova arrived at court as a maid of honor to the Empress Elizabeth, who had been a friend of her mother. Almost immediately, 15-year-old Dashkova aligned herself with 30-year-old Catherine, then a grand duchess married to the heir to the throne. The women shared two mutual passions: a love of French books and hatred for Catherine’s husband, Peter. Catherine was especially drawn to Dashkova’s drive to continually improve her mind through reading and cultural pursuits, long after her schooling ended. This very much matched Catherine’s intellectual prowess, and the two women often discussed new ideas.

The great blight on Dashkova’s adolescent life was her polar opposite older sister, Elizaveta. Hopelessly uncultured despite receiving a good education, Elizaveta was Peter’s paramour, and she hoped to one day replace Catherine as his wife. (This was not to be: After Catherine seized the throne in 1762, she had Elizaveta married off to a poor officer, consigning her rival to a miserable existence of poverty in the countryside.) Dashkova would never forgive her sister for bringing such shame to their family.

“Along with [Dashkova’s] political idealism, she was prudish and found her sister’s behavior a painful embarrassment,” writes historian Robert K. Massie in Catherine the Great: Portrait of a Woman. “Dashkova considered her to be living in vulgar public concubinage.”

In 1759, Dashkova made a much more respectable romantic alliance by marrying Prince Mikhail Dashkov, a second lieutenant in the imperial guard. Theirs was a love match, and the two shared mutual respect for each other—a fact that Catherine, trapped in an arranged marriage to an unfaithful, immature boor, likely envied. The couple had three children between 1760 and 1763.

A portrait of Dashkova by Pietro Antonio Rotari Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Dashkova's husband, Mikhail Dashkov Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Dashkova, Catherine the Great and the Enlightenment

Long-simmering tensions at the Russian court came to a boiling point in January 1762, when Peter succeeded his childless aunt, Elizabeth, as the new czar of Russia. Despite being raised in Russia as the heir to the throne, Peter much preferred his homeland of Prussia; he sought to reverse Elizabeth’s nationalist policies and situate Russia as deferential to Prussia.

Dashkova, a proud Russian, was one of many courtiers who refused to stomach Peter’s reforms. Certainly, the nobility wasted no time in getting rid of him. In June 1762, Dashkova participated in the coup that removed Peter from power and installed his wife, Catherine, on the throne. In the shadows, Dashkova and her husband gathered military support for Catherine’s cause, and they were at the ready when it was time to strike.

During the coup, Catherine famously rode out at the head of Russia’s army while wearing a man’s military uniform, symbolically presenting herself as a more competent leader than Peter. It was a clever romantic setup that Dashkova duly copied. “Here I was, dressed in uniform, with the red ribbon across my shoulder without its star, a spur upon one heel, and looking like a boy of 15 years of age,” the princess recalled in her memoirs. Within days, the deposed czar was dead; though the official cause was listed as “hemorrhoidal colic,” uncertainty surrounds Peter’s demise, with potential explanations ranging from assassination to suicide.

A painting of Catherine on the balcony of the Winter Palace on the day of the 1762 coup Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Instead of expressing gratitude for Dashkova’s allyship, the newly crowned empress grew increasingly jealous of her friend’s genius and talents, viewing her as a rival for prominence at court. Almost in retaliation, Dashkova openly expressed disapproval of Catherine’s promiscuity with men. She overestimated her influence with the empress, who turned to other advisers in matters of state.

In 1764, Dashkova—widowed following her husband’s death that August and by then thoroughly fed up with her diminished status at court—went into voluntary exile in Moscow. Five years later, in December 1769, she embarked on a tour of Europe, once again seeking to outdo her male counterparts. Most aristocratic men’s Grand Tours—voyages taken across Europe’s most sophisticated countries to absorb local culture—lasted just a few years. Collectively, Dashkova spent nearly a decade abroad, splitting her visits between two lengthy trips.

As the princess traveled through France and the United Kingdom, she collected such star acquaintances as her beloved Voltaire, English painter Georgiana Hare-Naylor, English actor David Garrick and Scottish historian William Robertson. The English author Horace Walpole could barely contain his fascination with her in a 1770 letter to his friend Sir Horace Mann.

A 1791 painting of Catherine's court Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

“Cooled as my curiosity is about most things, I own I am eager to see this amazon, who had so great a share in a revolution when she was not above 19,” Walpole wrote. “I have a print of the czarina, with Russian verses under it, written by this virago. I do not understand them, but I conclude their value depends more on the authoress than the poetry.”

But perhaps the greatest conquest Dashkova made on her travels was the American statesman Benjamin Franklin. “Dashkova, who rarely praised men, admired Franklin greatly; his brilliant mind, unassuming manner and straightforward appearance attracted her immediately,” writes Woronzoff-Dashkoff. Though the pair only met once, in 1781, they enjoyed a rewarding, multiyear relationship sustained mainly through letters. Impressed by Dashkova’s intellect, Franklin invited her to become the first female member of the American Philosophical Society in 1789.

When Dashkova returned to Russia in 1782, she quickly reconciled with the empress, who had missed her dearly and wasted no time in making peace offerings. They forgave each other for their trespasses and began anew. The following year, Dashkova began her tenure as director of the Imperial Academy of Sciences and Arts, a role which she threw herself into entirely, ushering the country into a golden age of scientific discovery and global prestige.

Benjamin Franklin in London in 1767 Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

A portrait of Dashkova in the 1790s Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Working together as a proper team at last, Catherine and Dashkova also established the Russian Academy, which was devoted to preserving and promoting Russian dialects and literature. As president of this institution, which later merged with the main scientific academy, Dashkova headed the publication of a six-volume dictionary. Even after so many years living abroad, Dashkova never shed a single ounce of her Russian pride.

Dashkova’s later life and exile

Catherine died on November 17, 1796, after suffering a stroke and falling into a coma. Her son and successor, Paul I, was perhaps one of Russia’s most controversial and tragic figures. It was something of an open secret in Europe that Paul was likely the biological child of one of Catherine’s lovers, Count Sergei Saltykov. Yet Paul remained emotionally attached to Peter, the father figure taken away from him when he was just a child by his mother’s coup. Catherine did little to instruct her estranged son in the way of leadership, so Paul spent his life feeling cheated of justice, attention and respect.

Following his accession, Paul wasted no time in weeding out undesirables, including anyone involved in the usurpation of his alleged father’s throne. He sent Dashkova away from court, barely giving her time to process her friend’s passing. Considering the turmoil of Paul’s short reign (he was assassinated by his own officers in 1801) and the wealth the princess had accumulated from her various properties and positions, this was hardly a staggering punishment.

A portrait of Paul I and his family Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Dashkova retired to her estate in Troitskoye, west of Moscow, where she lived out the rest of her days in relative comfort and ease. She certainly ruminated on her life, though perhaps not in the way the spiteful Paul expected. Encouraged by her female friends, she wrote her memoirs, which were composed in French and published in English and Russian in 1840 and 1859, respectively. Within the pages of the text, Dashkova puts to paper her feelings about the success of Catherine’s reign, in which she was such an active participant, and her sorrow at Paul’s spiteful efforts to unravel it:

My grief, I had almost said my despair, at a loss so irreparable as that which my country was called upon to suffer in the death of the empress, was not aggravated by any feelings of self-reproach from reflections on my own conduct, and the part I had uniformly acted; these were all indeed of a kind rather suited, in this moment of private distress, and alarming crisis of public affairs, to tranquilize and soothe my mind.

Dashkova’s extraordinary life ended in 1810, when she was 66. Unlike Catherine, the princess was never honored with the moniker “the Great.” But “Lady of the Firsts” would be a rather fitting substitute for a trailblazing woman who was centuries ahead of her time. Though Dashkova’s achievements have long been overlooked, she has received more recognition in recent years, including a 2006 American Philosophical Society exhibition about her relationship with Franklin.

As Woronzoff-Dashkoff writes, this “independent woman who dreamed of glory and political ambitions … demonstrated that women could do more than merely attend balls, run a household, serve their husbands and educate their children. They could take an active role in politics and be successful in a variety of areas traditionally dominated by men.”

The scholar concludes, “Self-sufficiency, self-reliance and a sense of one’s self-worth became her personal goals, as well as the cornerstones of her thoughts on education and the reconstitution of society for the realization of every individual’s potential.”

Catherine the Great's throne in the Winter Palace Vikramjit Kakati via Wikimedia Commons under CC-BY-SA 4.0

E.R. Zarevich is a history writer from Burlington, Ontario. Her work is published regularly by JSTOR Daily, the Archive and Early Bird

© 2024 Smithsonian Magazine Privacy Statement Cookie Policy Terms of Use Advertising Notice Your Privacy Rights Cookie Settings

Shared with Public

Sept 22, 2024 10am

Sunday Word 1

Change in Russia is coming. Frederick the Great knew how weak and misguided Peter III was, even though Peter III switched sides from France to support Prussia and England. Frederick the Great remarked "“[Peter] allowed himself to be dethroned like a child being sent to bed.”

.

By Spring of 1760, the wife of Peter III, Catherine [The Great], had assembled 3 powerful influencers all not knowing of the other. They were the Orlov brothers, former Russian Ambassador to Sweden Nikita Panin, and Dashkova, younger sister to Peter III's mistress. All were poised to strike, but not yet.

.

While George Washington is in his 2nd year as a representative of Frederick County Virginia in the House of Burgesses, Catherine is learning, planning, observing and organizing. Catherine was born Princess Sophie Augusta Frederica von Anhalt-Zerbst (2 May 1729 – 17 November 1796). She is 3 years older than George Washington. In 1760, he's 28. She is 31. She was 62 when she hired John Paul Jones in the Russo-Turkish War. The Crimea was won then. Also under her reign, Poland vanished when Russia, Austria and Prussia each took a piece of it. She also withdraws support for Prussia, undoing her deposed husband's alliance with Prussia.

.

Elizabeth Dies

Empress Elizabeth, the leader of Russia, dies 25 Dec 1761 (new 5 Jan 1762).

.

Peter III, the husband of Catherine, is made Emperor, who promptly switches sides to support Prussia and against France and Austria.

.

Catherine finds this moment of Empress Elizabeth's death to mourn in public by wearing a black ensemble that covers her pregnancy with Grigori Orlov, reputed for his enormous male endowment and his popularity with the Russian elite and the Russian military. His brothers are also influential and supporters of Catherine.

.

.

About the Date confusion

The Gregorian calendar was implemented in Russia on 14 February 1918 by dropping the Julian dates of 1–13 February 1918 pursuant to a Sovnarkom decree signed 24 January 1918 (Julian) by Vladimir Lenin.

.

The British empire adopted the Gregorian Calendar in 1752, dropping 11 days in September 1752, when Winchester VA was officially established as the name of Winchester.

.

.

The Coup

It isn't until 28 June 1762 (new 9 July 1762) Catherine's 3 groups of allies initiate the coup against her husband, Tsar Peter III, grandson of Peter the Great. Frederick the Great, appreciated Emperor Peter III for siding with him. Formerly, under Empress Elizabeth, Russia was an enemy in the Seven Years War. But Frederick the Great knew how weak and misguided Peter III was. He remarked "“[Peter] allowed himself to be dethroned like a child being sent to bed.”

.

.

That's it.

That's our lead story.

There's always more.

Skip around.

Read bits and pieces.

.

Table of Contents

.

Portrait

.

Catherine's 3 groups of allies in 1760

.

Sources

.

Article on Dashkova

.

.

Comments