Little Carpenter (Attakullakulla) gets around maybe

- Oct 30, 2022

- 15 min read

Updated: Jan 31, 2023

As we scour the events of 1758 in this year of 2022, we run into the Little Carpenter. His group of Cherokee are the last band of Cherokee who haven't left for home for the hunting season. The hunting wasn't just for sustenance. It was for debt too. The White Traders and the Cherokee were mired in debt. The Traders owed their suppliers. The Cherokee owed the traders for goods purchased on credit. This was a 50,000 deerskin trade annually. And how did those traders estimate how much credit to allow each Cherokee? They based it on that Cherokee's last haul. That last haul was used to predict how much they would bring in next time. That prediction determined how much credit could be given that Cherokee hunter.

If that pressure was not enough, just leaving the Forbes Expedition to go back home was a trial. There was horse stealing and killing and lies told about it all.

Little Carpenter and his men are the last band of Cherokee hanging in there with the Forbes Expedition. He's in Raystown 13 Oct 1758 and at end of October he's near Loyalhannon.

By the middle of November Little Carpenter and his men will be sitting in Winchester VA, stripped of their weapons, wondering how they're going to get home safely.

Before we track his whereabouts of late, take a look at a special moment among many of this man's life.

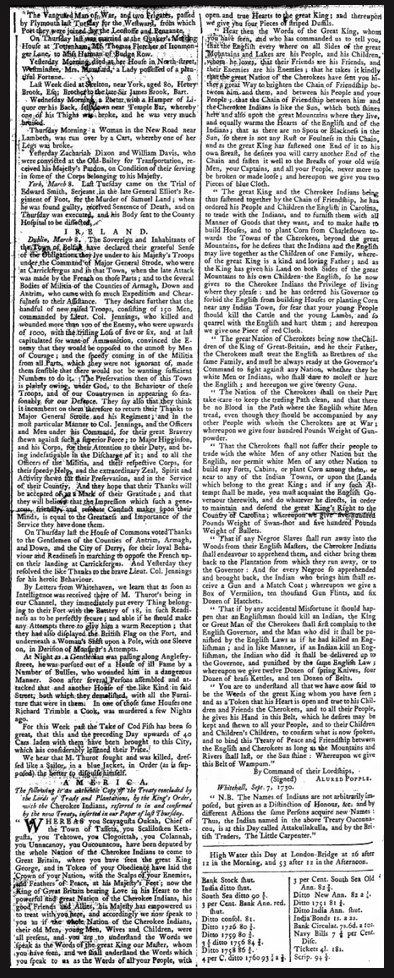

He's there on the far right in picture below when he visited London in 1730.

But the North Caroline Encyclopedia claims he is the center man in the picture.

He was first known as Onkanacleah. (page 4 of link)

And then later as Attakullakulla. James Mooney thinks Attakullakulla could be translated as "leaning wood", from ada meaning "wood", and gulkalu, a verb that implies something long, leaning against some other object.

No one is left alive in that picture by the time Attakullakulla goes to Charles Town (now known as Charleston SC) in 1759.

On 18 April 1759, he tells Gov Lyttleton

that he, Attakullakulla (Little Carpenter),

is, "the only one alive of those who went to see the Great King." See source.

The 7 leaders were: Attakullakulla, Oukah-Ulah, Clogoittah, Kallannah, Tahtowe, Kittagusta, and Ounaconoa.

Different Cherokee visited London in 1761.

A New Year's parade in London celebrates that fact.

So Little Carpenter is the last band of Cherokee hanging in there with the Forbes Expedition. But he and his men won't be for long.

October- November 1758 Whereabouts

Little Carpenter arrived at Raystown (called Fort Bedford only after 1 Dec 1758) on 13 Oct 1758.

That is one day after the French and their Indians attacked Loyalhannon (called officially Fort Ligonier only after 1 Dec 1758).

He's expected to go to Loyalhannon.

When does he arrive? Forbes claims Little Carpenter and his band left on 24 Oct 1758. But on the next day 25 Oct 1758, Forbes is guessing Little Carpenter might go to Loyalhannon any moment . . .

Finally . . .1 Nov 1758 he is really going to arrive at Loyalhannon.

"As the little Carpenter will be to morrow at Loyal Hannon The General desires that Seven Guns be fired for him—We expect to be there by one o’Clock . . . " Colonel Henry Bouquet datelines this letter to Colonel George Washington: "Camp at the East Side of Lawrell Hill 1st Novr 1758." Lawrell Hill is Bouquet's spelling of it. Washington always spells it Laurel Hill in his letters. Laurel Hill is the ridge east of Loyalhannon.

In his report of the guards for 31 Oct. (Orderly Book, 1 Nov., n.1), Lt. Col. Thomas Lloyd reported that “Capt. [Abraham] Bosomworth arrivd at about 12 A.M. with 30 Cherokees 8ber 31st 1758.”

Source:

So maybe Little Carpenter delayed until he felt the coast was clear. The French and their Indians were around. They had attacked with a relatively large force at Loyalhannon 12 Oct 1758. And then there's a friendly fire incident 12 Nov 1758 where Colonel George Washington's forces and Lt Colonel George Mercer's men fire at each other mistakenly. That happens almost right after George Washington's men finds a French and indian force at a campfire. Some prisoners are taken that change Forbes' mind to continue on with the Expedition.

Little Carpenter and his Cherokee band stays around the area until 19 Nov 1758 when he leaves what is called New Camp to go back to Loyalhannon.

General Forbes is incensed.

He writes to James Burd, operating commander of Loyalhannon, about the “villainous desertion,” ordering Burd to send messengers to Raystown, Fort Cumberland, and Winchester to intercept the Indians so that the arms, ammunition, and horses given them could be recovered (James, Writings of Forbes, 256–58).

Once Little Carpenter and his men are stripped of the weapon, they must now look at the prospect of heading home unarmed.

He's in Winchester VA wondering now about their own safety.

More on that.

But for now, that's it.

That's our lead story.

There's always more.

Skip around.

Read bits and pieces.

Compiled and authored by Jim Moyer 10/30/2022, updated 10/31/2022, 1/31/2023

.

.

.

.

Sources

50,000 deerskin trade annually

Page 6, The Cherokee Frontier, Conflict and Survival 1740-1762, by David H Corkran, published by University of Oklahoma Press 1962, paperback published 2016

Horse Stealing

On 18 April 1759, he tells Gov Lyttleton that he, Attakullakulla (Little Carpenter), is, "the only one alive of those who went to see the Great King."

Source page 167, The Cherokee Frontier, Conflict and Survival 1740-1762, by David H Corkran, published by University of Oklahoma Press 1962, paperback published 2016

Cherokee in New Year's London Parade

Forbes Expedition

1 Dec 1758 is when Forbes officially dubbed Raystown as Fort Bedford and Loyalhannon as Fort Ligonier.

Prior to that all correspondence by officers referred to both places only as Raystown or Loyalhannon.

Page 179

The British Defeat of the French in Pennsylvania, 1758: A Military History of the Forbes Campaign Against Fort Duquesne: by Douglas R. Cubbison. More on this author here. And a review here.

Little Carpenter bio

Forbes letter of 19 Nov 1758

History of the Cherokee Indians and their legends and folk lore byStarr, Emmet 1921

Discussion of the cycle of debt and of Little Carpenter's whereabouts

Little Carpenter wanted black slaves as helper to his wife

In March of 1758 and a year later 1759 battles out west

Cherokee Chieftains at the British Court

16 September 2016 By Hunter S. Jones

In June 1730, seven Cherokee Chieftains landed at Dover, aboard an English Man-o-war. They had come to meet the King. Hunter S. Jones tells us why.

The Native American Tribes have historically made a global impact due to their nobility of spirit. Few have remained in the modern consciousness like the Cherokee Nation. This may be due to the fact that during early contact with Europeans, many of the tribal leaders recognized that the only way to survive was to change. This adaptability led to two council meetings with the Kings of England.

The first Anglo-Cherokee contact might have been in 1656, when English settlers in the Virginia Colony recorded that six to seven hundred “Mahocks, Nahyssans, and Rechahecrians” had encamped at Bloody Run, now Richmond, Virginia. They were driven off by a combined force of English and the Pamunkey Tribe. A few historians believe that the attacking tribes match with what is now known of the Cherokee at that time.

Then, in 1673, two Englishmen, James Needham and Gabriel Arthur, were sent to Overhill in Cherokee country from Fort Henry, which is now Petersburg, Virginia. The English wanted to build a direct trading connection with the Cherokee to bypass the Occaneechi Indians, a tribe that inhabited the Piedmont Region of what is now North Carolina and Virginia and were serving as middlemen on the Trading Path. The two colonial Virginians eventually made a connection with the Cherokee. By the late 17th century, colonial traders from both Virginia and South Carolina were making regular journeys to Cherokee lands, but by the 1690s, the Cherokee had founded a much stronger and important trade relationship with the colony of South Carolina.

Little written documentation remains to chronicle these experiences in Charles Town, (known today as Charleston. The events of the early colonial trading period have been put in place by historians who have examined the records of laws and lawsuits involving trade with the Cherokee. The mainstays of trade were deerskins in exchange for knives, firearms, and ammunition. In 1705, traders lodged complaints, stating that their business had been lost to the Indian slave trade, which had been overseen by the Lord Proprietor of the colony, James Moore. Moore had sent bounty hunters to “set upon, assault, kill, destroy, and take captive as many Indians as possible.” When the captives were sold, the profiteers divided the proceeds with the governor.

However, the Cherokee continued to work through diplomacy with the “newcomers.” They allied with the British in fighting the Shawnee Tribe (allies of the French) and battled again beside the British in 1712-1713 against the Tuscarora Tribe. The aftermath of these battles saw the beginning of a Cherokee-British alliance that endured for the majority of the 18th century, despite numerous rebellions and uprisings as the Cherokee fought to keep colonial settlers away from their ancestral lands.

In 1721, the Cherokee agreed to sell land between the Saluda, Santee, and Edisto rivers to the first Royal Governor of South Carolina. This exchange served to establish a boundary between the Cherokee territory and the colonists. Since it was the first time the Cherokee had given any land to any European power, it signaled a great step in terms of negotiation and future trading.

A peace was maintained in the years that followed. Sir Alexander Cumming of England was encouraged to visit the Cherokee, reportedly based on a dream his wife had one night. He sailed to America, arriving at Charlestown on December 5th, 1729, and by March 11th, 1730, he began the journey to Cherokee country. (Later, it became evident that his travel was actually based on own moneymaking scheme.) At Keowee, Cumming met a Scottish trader named Ludovic Grant, who had resided at the Cherokee settlement of Tellico since 1720, had married a Cherokee woman and spoke their language. Cumming and Grant made the journey into the centre of the Nation; a trip of over one hundred and fifty miles. Reports state that he never stopped longer than one night at a single location.

Sir Alexander was told of the ceremonies that made a warrior a chieftain, or ouka. This word translated into English as king. The chieftain was given a cap of red- or yellow-dyed opossum skin, which was interpreted as crown. Sir Alexander asked if he could take a crown to England and present it as a gift to the English King. In an article in the London Daily Journal of October 8, 1730, he made claims to have been made a chief of the tribe. Cumming further claimed that he had been allowed to name Moytoy of Tellico as the Emperor or King of the Clans.

He told the Cherokee he would be returning to England and that if they would like to accompany him, he would take them to meet his King.

Seven Cherokees expressed their willingness: Attakullakulla, Oukah-Ulah, Clogoittah, Kallannah, Tahtowe, Kittagusta, and Ounaconoa. They arrived at Charlestown on April 13, 1730, and on June 5th, they landed at Dover, England, on the English man-of-war, Fox.

On the 22nd, they were presented to George II. Sir Alexander laid the Cherokee opossum-skin crown that the chieftains had made at his King’s feet, and the Cherokees added four scalps and eagle tail feathers to the tribute.

After four months in England, the Indian chieftains signed a formal treaty with Great Britain. This was known as the Articles of Friendship and Commerce, and it recognised the Cherokee nation as subjects of the crown. The treaty standardised trade between the two nations and made Cherokee land available for British settlement. A British newspaper praised the treaty, in which it was stated, “The signing of these Articles…will strengthen the hands of his Majesty’s subjects… for these people are formidable.”

Reports of the visit were popular in the London press:

Weekly Journal, or The British Gazetteer, 27 June 1730: On Monday last the Indian King, and the Prince, and five of the chiefs of his Court (all blacks) were introduced to his Majesty at Windsor, the King had a scarlet jacket on, but all the rest were naked, except an apron about their middles, and a horse’s tail hung down behind; their faces, shoulders, &c. were painted and spotted with red, blue, and green, &c. they had bows in their hands, and painted feathers on their heads; a dinner, viz. a leg of mutton, a shoulder, and a loin of mutton was provided at the Mermaid at Windsor for them; the King lies on a table in a blanket; but the Prince, and the chief of his Court, lie on the ground.

London Journal, 15 August 1730: The day before the Indian Chiefs left Windsor, they went to take their leave of the Court, at which time his Majesty was pleased to present them with a purse of one hundred guineas. On Wednesday the Indian King and his retinue, in their return from the Tower, were regaled in an handsome manner by several merchants of this City trading to South Carolina, at the Carolina Coffee House in Birchin-Lane, where a great number of gentlemen resorted to see them, they being on their return home, which it is believed will be in about three weeks’ time; and his Majesty’s ship, the Fox, is now refitting at Deptford in order to receive them. On Thursday the Indian Princes went to Tottenham-Court Fair, and were entertained with the several diversions that place afforded. Cumming did not spend much time with the Cherokees in England. After the treaty was signed and the Cherokees were sent back to South Carolina, Cumming made appeals to King George II asking to be appointed as overseer of the Cherokee Nation. These appeals were unsuccessful and in 1737, his schemes of defrauding colonists in Charleston were discovered, and he was sent to Fleet Prison. On October 8th, the Chiefs sailed to South Carolina loaded with gifts from the government. It was reported in the London newspapers that they arrived safely on February 18, 1731.

The unification of the Cherokee Empire and crowning of a single king was ceremonial. Once the chieftains returned to their homeland, the authority remained clan based. However, the voyage to London and the treaty were to play an important role in the Cherokee-British alliance.

The Cherokee and British were allies during the French and Indian War. Unfortunately, relations soured when British soldiers murdered a number of Cherokee warriors, with plans to claim their scalps as those of the French. The Cherokee retaliated by attacking British settlements in North Carolina, taking the same number of male lives in retribution. Future attacks by British armies destroyed dozens of Cherokee towns in what is now Tennessee.

“As to the manners of the Indians, I grant they have been often represented, and yet I have never seen any account to my perfect satisfaction,” wrote Virginian Henry Timberlake, a lieutenant in the British Army in Memoirs, penned in 1765. The book outlines his life among the tribe at the end of the French and Indian War. Timberlake stayed in the Overhill towns of the Little Tennessee River Valley for months. He attended town councils, dances, and feasts, living in the home of Chief Ostenaco. In 1762, Ostenaco and two other Cherokee leaders, Cunneshote and Woyi, asked him to take them to London in order to meet with King George III. “The bloody tommahawke, so long lifted against our brethren the English, must now be buried deep, deep in the ground, never to be raised again,” said Ostenaco. The group set sail for England in May 1762. The Cherokee delegation’s visit to London helped to secure the Proclamation Line of 1763, which forbade white settlers from claiming land west of the Appalachian Mountains.

In 1715, the population of Cherokee was listed by the South Carolina Colony as over ten thousand in thirty villages. As they grew, so did their relationship with their trade partner. They came to know and accept the newcomers, and the assimilation evolved as they came to welcome the cultural changes that the British brought them. They started to dress more European, and even adopted many of their farming and building methods. During the American Revolution, the Cherokee Indians supported the British soldiers and assisted them in battle. As the United States grew and developed, the Cherokee changed with it. Many had begun moving westward following the Revolutionary War. In 1828, gold was discovered in Georgia on the Cherokee’s land. This prompted the overtaking of their homeland, with the remaining Cherokee forced out. They were made to leave because their lands were needed as America grew, citizens from the east coast were eager to find a new place to homestead, and the gold made the land attractive. This historic removal is now called the Trail of Tears or the Trail Where They Cried. Men, women, and children left their homelands, walking thousands of miles in the custody of Federal Troops to the present day Cherokee Nation in the state of Oklahoma. It began in 1828, and when the last one was completed in 1835, approximately 4,000 Cherokees and their family members had lost their lives on the 116-day journey from the Appalachian Mountains to the western frontier. Once they had arrived in Oklahoma, the tribe members who signed the treaty agreeing to the removal were assassinated by surviving members of the tribe.

Today, the Cherokee maintain a strong sense of pride in their heritage. The largest population of Cherokee Indians live in the state of Oklahoma, with the smaller Eastern Band residing in the hills of the Smokey Mountains of North Carolina.

Deb Cookson Hunter writes as Hunter S. Jones. She is a direct descendent of Joseph A. Cookson, who is listed on the Henderson Roll of 1835. This is a census of Cherokees and their families – mulattos, quadroons and whites – who were removed to Oklahoma under the Treaty of New Echota. It is also called the Trail of Tears Roll. Originally from Chattanooga, Tennessee, she now lives in Atlanta, Georgia with her Scottish born husband.

Source:

Source of 1730 Treaty reprint

To George Washington

from John Forbes,

19–20 November 1758

From John Forbes From the Camp where they are Building the Redouts. just arrived 2 aClock afternoon1 [19–20 November 1758]

Sir The Catawbas & those Indians that came with Crohgan, I have persuaded to march forward and join you were it never so late this night, the Cherokees are not come up.2 I know nothing of how far you go this night or where you make your last stop, so as by this time Colo. Bouquet must have joined you I suppose all that is settled. Be therefore so good, as send me back with a fresh Horse, where you are, this night, where you go to morrow,3 What orders Colo. Montgomery has, and as far as you have learned, the distances of the places before you as well as those distances from this forward to you, Turtle Creek &c. and where you intend to push for, that wee may assemble and proceed togather I have sent forward 30 head of Cattle from the 90 that came from Loyll Hanning with the last Division, they have orders to make no stop untill they reach you. I shall order Col: Montgomery to strengthen their escorts I never doubted of the ennemys scouting partys discovering us, but I think it highly necessary that wee discover them likewise, as also the sure Knowledge, if ever they send out any force from their fort capable of Attacking us I could not well join Montgomery this night, but shall if possible to morrow, for which reason if he is not absolutely necessary up with you his making a Short march to morrow will give me ane opportunity of joining him to morrow night, and wee can join you next day.

The Stillyards &c. were sent you ⅌ express 2 days ago, I have sent another express back to hasten up the Carpenter. I have orderd 40 of the Waggon horses that arrived yesterday at Loyll Hanning (Which are very fine) to be directly sent off with light loads of Flour in order to make the train quite easy—And as there are a great number of Bats horses loaded with flour I should think the men ought to be putt again to their old Allowance, for otherwise our Cattle will not do and wee have flour enough.4

Croghan has sent off 3 of his Indians towards the Ohio for Intelligence, and Jacob Lewis that Colo. Armstrong sent out last thursday is just come in without having done, or learning any one thing.5

If Col: Bouquet chooses that Colo. Montgomery should halt ane hour or two for me to morrow morning, let him send him back orders by the return of this express to night or order him a Short march & I can join him and bring Cattle Artillery and all in with us. This must serve as ane answer to Colo. Bouquet and your letters that I receivd this morning,6 wrote in my litter so excuse Yr Most obseqs &c. Jo: Forbes. ALS, British Museum: Add. MSS 21640.

1. Forbes came on 19 Nov. to Armstrong’s New Camp with Col. Archibald Montgomery and his Highlanders from Loyalhanna, leaving Col. James Burd of the Pennsylvania Regiment at that place in command of a force of nearly twelve hundred men, many of them ill. Forbes wrote “20th Nov.” at the end of the letter, suggesting that perhaps he did not finish writing it until after midnight.

2. For the small party of Indians that George Croghan brought to Forbes on this day from the conference at Easton, see Orderly Book, 3 Nov., n.5.

Only a few of the large number of Cherokee who had come up in the spring and summer were still in Pennsylvania when Little Carpenter arrived at Raystown on 13 Oct. with thirty of his Cherokee warriors along with thirty Catawba Indians (Forbes to Richard Peters, 16 Oct. 1758, in James, Writings of Forbes, 234–37).

On 21 Oct.

Forbes reported to Bouquet from Raystown that he had “engaged the Little Carpenter with upwards of Eighty of the very best of the Indians to accompany us” (ibid., 241–42).

Three days later

he wrote Gen. James Abercromby: “Our Indians I have at length brought to reason by treating them as they always ought to be, with the greatest signs of scorning indifference and disdain, that I could decently employ, So the Little Carpenter with 100 good Indians, all well fitted for war are gone to our advanced post of Loyal Hannon, ready to act as desired” (ibid., 244–47);

but on the next day, 25 Oct.,

Forbes wrote Bouquet at Loyalhanna: “The Catawbas marchd Monday with some Cherokees. . . . I do not know what to say to the Carpenter but I believe he will Come with me” (ibid., 248–50). Little Carpenter and about 30 Cherokee did go up to Loyalhanna at the end of October, arriving shortly before Forbes got there on 2 Nov. (see Bouquet to GW, 1 Nov., n.2).

After writing this letter to GW from New Camp on 19 Nov.,

Forbes discovered that Little Carpenter with nine or ten of the Cherokee had left New Camp and were headed back toward Loyalhanna.

Forbes immediately wrote, still on 19 Nov.,

to Col. James Burd at Loyalhanna about the “villainous desertion,” ordering Burd to send messengers to Raystown, Fort Cumberland, and Winchester to intercept the Indians so that the arms, ammunition, and horses given them could be recovered (James, Writings of Forbes, 256–58).

3. GW was at a “Camp Near Turtle Creek” (Orderly Book, 19 Nov.) on the night of 19 Nov., and on 20 Nov. he was busy setting up the post for the army at Turtle Creek, to be known as Washington’s Camp. Bouquet joined him at the camp on 20 Nov. (see Orderly Book, 20 Nov., n.2).

4. For the “old Allowance,” see Orderly Book, 12 November.

5. Jacob Lewis may have been the man of the same name who was a carpenter and tax assessor in Philadelphia. “Last thursday” was 16 November.

6. He is undoubtedly referring to GW’s letter of 18 Nov., but Bouquet’s letter has not been found.

Source:

Sources

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Comments